As A/EM students and researchers, we are often conscious of our difference or uniqueness within academia. Even more so, when our identities sit at an an intersection between ethnicity and other marginalised identities. We may find ourselves called up to speak for our communities, regardless of whether we feel that it is our place to, or feel burdened by the thought that how we present ourselves as individuals being a representation of our culture at large. In this month’s blog, Marlowe Toledo, encourages us to reframe this thinking and start to consider this ‘burden’ from a more critical perspective.

Over the last year, I’ve focused my academic research on issues that affect me and the communities I belong to, most prominently queer and ethnic communities. Even within these communities I am often an outlier: I’m the only trans person, I’m the only person outside of the gender binary, I’m the only person from Latin America. Students and researchers that belong to marginalised communities are often outliers in academia, and for those who also experience other axes of oppression the feeling is often that not only are we alone in the spaces we occupy, but also that this causes the burden of representation to fall on us.

The fact that academic spaces are, in its majority, made up of white, heterosexual, cisgender men will probably not be news to any reader. Young queer people of colour are growing their presence in a myriad of fields, and although many of us are not trailblazers or the first of our kind, we are often the first people in our family to complete higher education, or the first generation to do so in New Zealand. We are often representative of a new generation that speaks loudly and clearly about researching what is important and relevant to people like us. We are spokespeople for our cultures, our identity, our peers and our families.

While that is a position of privilege to be in, to be in a place considered out of reach to the majority of people like us, it is also a daunting task to not fail them and, to a certain extent, speak for them. Precisely because of our position of privilege as people who have achieved or are achieving higher education, we cannot be complete representatives of our communities; and precisely because of how out of reach this position is considered to be, the pressure to succeed and continue to climb higher results in fatigue and a fear of failure.

However, rather than aiming to be a spokesperson for our communities, which are rich with different experiences and lives, or burning ourselves out, our goal should be that being the outliers is something that happens less and less often. The burden of representation is not the result of people attempting to speak on behalf of their entire communities, but a consequence of the power structures at play that create difficult situations for individuals that differ from the norm. Rather than placing the burden on us as individuals, we should question why we have to shoulder the burden in the first place.

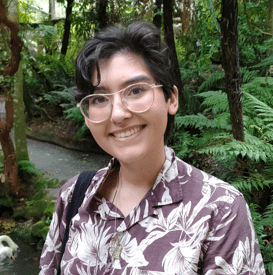

About the author

Marlow Toledo (they/them)

mtol907@aucklanduni.ac.nz

Marlowe is a non-binary tauiwi in Aotearoa, originally from Brazil. They are currently pursuing a Masters in Communication, and their thesis looks into self-representation of intersectional ethnic youth on social media and the public discourse that surrounds it. Their research interests include online communities and behaviour, queer and immigrant youth, and representation in popular media.